A Birthday to Remember

Celebrating History, Flavor, and Gratitude at Dōgon in Washington, D.C.

As you add birthdays, gratitude takes on new dimensions. First and foremost, you made it! This year, I wanted to celebrate it in Washington, D.C. It has museums, history, and a food scene with soul. I had one restaurant in mind—Dōgon in the Salamander Hotel.

It was a very specific choice for so many good reasons.

I don’t eat out just for the food. Not even for a Michelin star or stars. I’d rather cook at home, where I know what I’m eating. If you care about your health, I think that’s a better approach. But if you do go out, make it count, even if a few calories go on the plate. Dōgon more than counted.

What drew me there was Notes from a Young Black Chef by Kwame Onwuachi, a memoir Amazon recommended. It’s a gripping account of a young man navigating drugs, grief, racism, and the brutal realities of the restaurant world—but also talent, tenacity, and family. Food, his mother, and his sister became steady lifelines. His path from hardship to success felt honest and earned, and made me want to support what he’s building. His New York City restaurant, Tatiana, is a standout. Getting a reservation online seemed hopeless.

Dōgon was more accessible given I was staying at the Salamander hotel. The restaurant was inspired by two forces: 1) the Dogon tribe of Mali, known for their rich cultural traditions and early astronomical knowledge and 2) Benjamin Banneker, the self-taught mathematician, astronomer, and scientist who published almanacs, because he may have had ancestors from this region (though this remains a matter of conjecture).

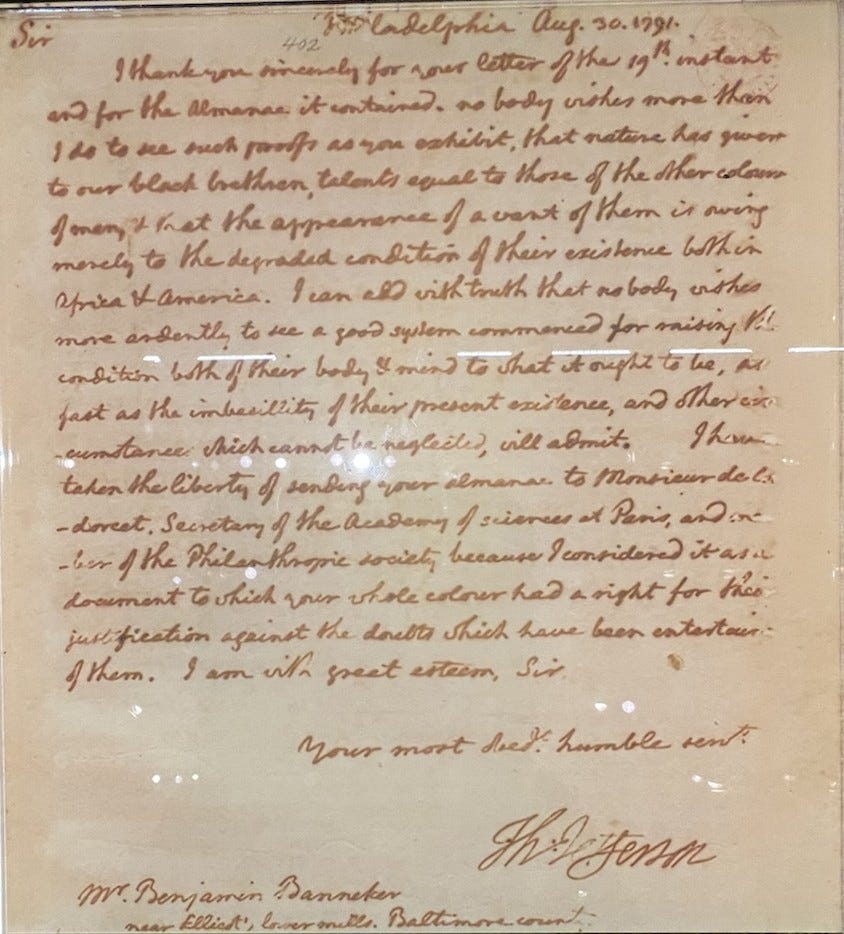

Banneker was bold and brilliant, writing Thomas Jefferson to ask how a nation could declare all men equal while upholding slavery. Jefferson wrote back, acknowledging Banneker’s intellect but sidestepped the deeper issue he raised.

(This letter was on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. It is part of the collection at the Library of Congress.)

Sculptures of Banneker and Jefferson appear on the first floor of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. They stand just feet apart—frozen in time, embodying conviction and contradiction. That image stayed with me.

It’s worth noting that after Pierre L’Enfant was dismissed from the Washington, D.C. project, Banneker assisted Andrew Ellicott in surveying the boundaries of the federal district that would become the capital.

With a history like that, the cuisine should be historic, and it is. Inspired by West Africa and Caribbean cuisine, Dōgon’s menu is flavorful and precise to its schema. The cornbread was light and airy, and the spicy butter added just the touch.

Next up was the crab. It was lightly crisped on the outside and soft inside, paired with small silver dollar-sized pancakes and a sauce that pulled it all together. It was a composition dish, the elements of which contributed to a richer whole. It gave me ideas for my kitchen: crab cakes with almond crunch, perhaps a yogurt-based sauce.

Phil’s cabbage arrived in a shallow bowl of hot and sour broth. I had doubts, but one spoonful changed my mind — mellow heat, perfectly tender cabbage with golden seared edges. He was surprised. It was an unusual presentation, but a delicious one.

I ordered the fish, which arrived already filleted, refined and delicate—no bones, no heaviness. Just clean, thoughtful food.

I asked the waiter about the seafood.

“Where’s the branzino from?”

“New Zealand.”

“Oysters?”

“Virginia.”

“Ahi tuna?”

“Japan.”

Everything had its origins — and it tasted better for it.

Phil said the menu was not large, but it was well composed, a little symphony of tastes leading to an overall harmony. “The customer can’t make a mistake. No matter what they order, it all produces a wonderful meal.”

We ended with a rum cake, its hard shell sealing in a moist and fragrant center cake. I had a bite. It was a splurge, and I smiled.

Phil beamed across the table and wished me a happy birthday.